For centuries, the worlds of literature and liquor have intertwined in ways that spark endless curiosity. Writers from Shakespeare to Kerouac have turned to whiskey, wine, and everything in between not just for escape, but as a catalyst for creativity, a companion in the quiet hours, and sometimes a muse in disguise. What draws these artists to the bottle? How did figures like Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald summon their imaginations with specific sips, long drinks, or sharp shots? In exploring this enduring bond, Hemingway stands out as a towering presence, his life and work soaked in the stuff, revealing as much about the creative process as any blank page.

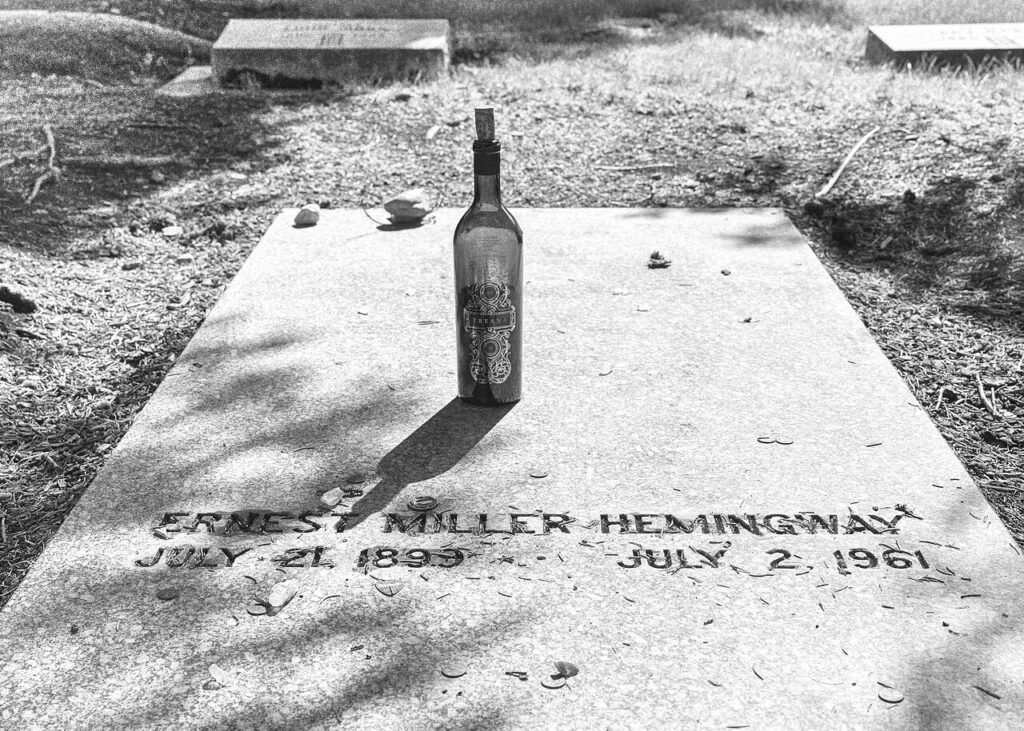

Ernest Hemingway, the Nobel Prize-winning author behind masterpieces like The Sun Also Rises, The Old Man and the Sea, and For Whom the Bell Tolls, embodied the archetype of the hard-drinking literary giant. His rugged persona, forged in war zones and fishing boats, often included a tumbler in hand, but his relationship with alcohol evolved from disciplined indulgence to something far more consuming. In his youth, Hemingway approached drinking with a measure of restraint that mirrored his precise prose. He favored wine above all, savoring its simplicity during off-hours with friends, yet he drew a firm line at the writing desk. Mornings belonged to the work, sober and unrelenting. As he once quipped, “I have been drunk 1,547 times in my life, but never in the morning.” This ironclad routine kept the bottle at bay while the words flowed, a testament to his belief that true creation demanded clarity.

Yet as the years wore on, that boundary blurred. Hemingway’s tastes shifted, and so did the quantities he consumed, a pattern echoed strikingly in his fiction. Literary scholar Claudia Wankmüller-Kiefer, in her dissertation on “Hemingway and Alcohol,” traced how the characters in his stories mirrored their creator’s descent. Early works portray drinking as pure hedonism, a joyful release amid life’s adventures. But in his later novels, protagonists grapple with alcohol’s darker pull, aware of its destructive edge yet turning to it anyway to drown sorrows, fears, and the weight of existence. This parallel was no coincidence. Hemingway’s own intake escalated with age, from social sips to relentless pours, transforming a vice into a vital thread in his narrative tapestry.

No corner of Hemingway’s world pulses with booze quite like his Paris years, captured vividly in his expatriate tales. In The Sun Also Rises, his 1926 debut novel, a band of young American expats guzzles red wine by the gallon, the pitchers refilled endlessly in sun-drenched cafes. One gallon equates to roughly 3.8 liters, and the text lingers on these excesses, painting a portrait of carefree revelry that barely conceals underlying restlessness. His memoir A Moveable Feast, published posthumously, revisits those bohemian days with even more indulgence. Here, the Seine-side salons brim with whiskey, champagne, and assorted wines flowing freely among Hemingway’s circle of writers and artists. Hangovers become folklore, and remedies veer into the absurd: a splash of whiskey mixed with aspirin, prescribed for everything from colds to creative blocks. If it worked, who was to argue?

Hemingway’s personal encounters with the bottle often led to regrets, sharpening his wry self-awareness. Drinking loosened his tongue, sparking outbursts that clashed with his otherwise stoic demeanor. He learned to temper this the hard way, advising himself and others with the gem: “Always do sober what you said you’d do drunk. That will teach you to keep your mouth shut.” Letters to his close friend F. Scott Fitzgerald brim with apologies for such lapses, descriptions of pounding headaches giving way to remorseful clarity. These moments humanize the myth, showing a man who chased inspiration through haze but paid the price in the light of day.

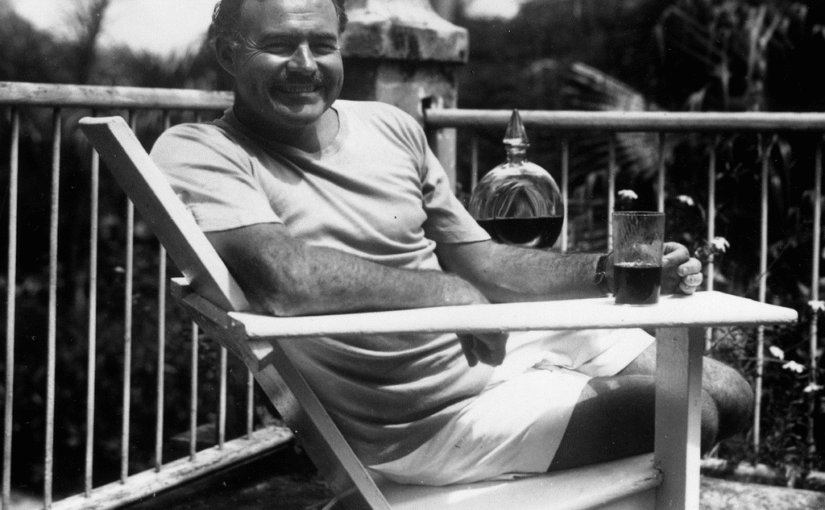

Beyond Paris, Hemingway’s thirst found legendary haunts in the tropics and the Keys. In Havana, Cuba, where he spent formative years during the 1930s and 1940s, El Floridita bar became a second home. Tucked along the bustling Obispo Street, its dim lights and mahogany counters drew the writer like a magnet. Here, amid the swirl of cigar smoke and salsa rhythms, Hemingway held court, trading stories with locals and expats alike. The bar claims him as its eternal patron, and photos still capture his broad frame hunched over the counter. Across the Florida Straits in Key West, Sloppy Joe’s bar laid similar claim to his loyalty. Legend has it Hemingway suggested the name himself, a nod to the sloppy joes served there, though the spot had humble roots as a speakeasy during Prohibition. Night after night, he philosophized over drinks with luminaries like John Dos Passos, Waldo Peirce, and a cadre of adventurers, from sea captains to fellow scribes. These watering holes weren’t mere pit stops; they fueled the raw energy of his later works, blending camaraderie with the solitude of the soul.

At the heart of Hemingway’s bar lore lies his signature sip: the Hemingway Daiquiri, or as insiders call it, the Papa Doble. Born in El Floridita, this cocktail owes its fame to bartender Constantino Ribalaigua Vert, who tailored it for his famous regular. The base is straightforward, rum shaken with fresh lime juice and simple syrup, evoking the island’s heat. But debates rage over the authentic recipe, even today. Online variations swap rum for gin or whiskey, straying from the original’s spirit. Whispers persist that Hemingway demanded his version unsweetened, doubled up on grapefruit juice, and laced with a touch of maraschino liqueur for a tart, bracing kick. No sugar to dull the edge, just pure, punchy flavors that matched his unyielding style. Papa Doble, a nickname from his Cuban friends, encapsulated this tweak, turning a classic into a personal elixir.

This preference for simplicity aligned seamlessly with Hemingway’s aesthetic, both in ink and ice. His writing stripped sentences to their bones, lakonic and lean, shunning flourish for truth. Drinks followed suit. Contemporaries recalled him swigging straight from the bottle on fishing trips or rough nights, bypassing the frippery of garnishes or mixes. Modern renditions of the Hemingway Sour, with their colorful umbrellas and sugared rims, feel like distant cousins, a far cry from the man’s no-nonsense pour. He craved the essence, the burn without distraction, much like the iceberg theory that underpinned his prose: show the tip, imply the depths.

Hemingway’s saga with spirits extended far beyond these famed spots, of course. As one of literature’s most notorious imbibers, he left footprints in bars from Pamplona to Paris, each claiming a piece of his legend. Yet it’s this very excess that cements his place in the pantheon, a writer whose glass reflected the storms within. His drinking was indulgence, yes, but also mythology, a lens into the contradictions that drove his genius: the discipline warring with desire, the clarity clashing with chaos. In the end, Hemingway’s legend endures not despite the bottle, but because of it, blurring the line between man, artist, and the myths we pour for ourselves.

Header image: Photograph of Ernest Hemingway at the Finca Vigia, his home in Cuba. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.