The act of writing has long been associated with a certain romantic misery, and nowhere does this ring truer than in the timeworn link between literature and strong drink. In smoky bars, sun-soaked cafés, or tucked away in solitary studies, some of the world’s most acclaimed authors have reached for the bottle as readily as for the pen. Their tipple of choice was rarely incidental, and sometimes it was every bit as iconic as their work. Today, let us slip into the heady world of famous writers and their favorite drinks, toasting not only their literary brilliance but the cocktail of creativity, chaos, and sometimes tragedy that marked their journeys.

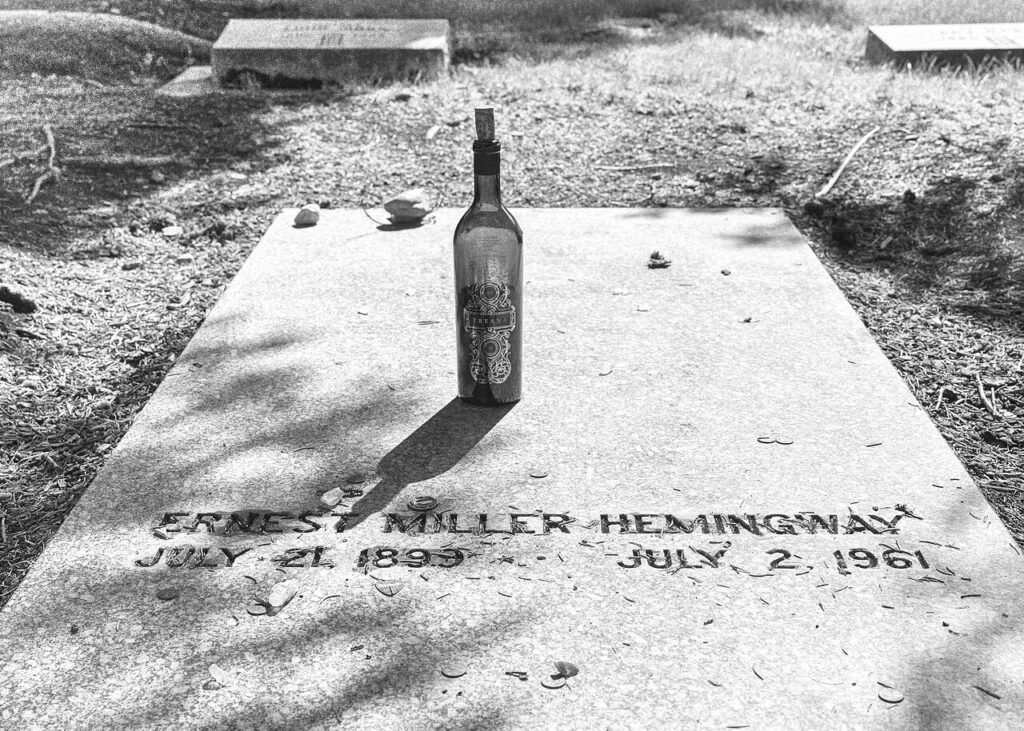

Ernest Hemingway: Papa Doble and Mojito Mornings

Ernest Hemingway’s life is the stuff of legend: risk-taking, globe-trotting, and always awash in both adventure and alcohol. The author of The Old Man and the Sea and A Farewell to Arms turned drinking into a kind of performance art. His go-to was the Daiquiri, not just any Daiquiri, but the infamous “Papa Doble,” a turbocharged version of the Cuban classic, heavy on the rum and light on the sugar. The mojito, that quintessentially Caribbean blend of rum, lime, and mint, also adorned Hemingway’s afternoons, and martinis were often on the menu for evenings.

Yet, in the end, the writer’s bravado in both literature and drinking masked an encroaching darkness. Depression hounded Hemingway, and despite, or perhaps because of, his reliance on liquid courage, he died by suicide in 1961, his final act as stark as any on the page.

F. Scott Fitzgerald: Gin Rickeys and the Jazz Age

If the Roaring Twenties had a signature cocktail, the Gin Rickey would likely take pride of place, thanks in no small part to F. Scott Fitzgerald. The author of The Great Gatsby was rarely pictured without a glass in hand, believing gin would betray him less perceptibly on his breath. Legend (and Chapter 7 of Gatsby) confirm that Fitzgerald’s taste for this refreshing mix of gin, lime, and soda kept him in perfect sync with the jazz, sparkle, and underlying emptiness of his age.

Unfortunately, Fitzgerald’s personal life had the fizz of a Gin Rickey but none of its aftertaste. The highs of literary celebrity gave way to instability, hospitalizations for his wife Zelda, and a slow descent fueled by drink. Fitzgerald died at 44 of a heart attack, still, in his own ironic words, “a great writer in spite of myself”.

Charles Bukowski: Boilermakers and Barflies

Charles Bukowski, poet laureate of urban grit, chronicled life’s dirty details from behind a haze of cigarette smoke and spilled beer. His books, Post Office, Factotum, are love letters to the downtrodden, and their author made no apologies for his philosophy of, shall we say, robust self-medication. His favorite, the Boilermaker (a slug of bourbon plunged into beer), mirrored his approach to literature: simple, bracing, and likely to leave a mark. Whiskey and beer were his steadfast companions, aiding Bukowski on a long walk through life’s gutters and alleys.

The cost, however, was high. While Bukowski outlived many of his contemporaries, his health was persistently battered by years of excess. Yet, for better or worse, he wore his vices on his sleeve, with a defiant shrug at a world that looked askance at both his drinking and his art.

William Faulkner: Mint Julep Meditations

Southern Gothic never tasted so sweet, or so bracing, as when William Faulkner put pen to paper, often lubricated by a Mint Julep or a glass of whiskey. The man behind The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying relied on alcohol as both muse and medicine. He claimed that “civilization begins with distillation,” and who are we to argue with a Nobel laureate? The julep’s cool clarity, muddled with mint, mirrored Faulkner’s best prose: layered, elliptical, and strangely intoxicating.

Faulkner battled the demons of alcoholism for much of his career, periodically drying out only to tip back in again. His struggles rarely eclipsed his genius but left their signature, at times, on both his work and his family life.

Jack Kerouac: On the Road to Mezcal

The “King of the Beats,” Jack Kerouac wound his way across America and the page with equal speed, always ready for a drink at the next stop. His “On the Road” lifestyle was defined by improvisation, exploration, and a thirst for both experience and spirits. Kerouac favored the Mezcal Margarita, as well as whiskey and beer, whatever kept the words, and the evenings, flowing freely.

But beatnik bravado was shadowed by personal tragedy. Kerouac’s final years were marked by declining health and isolation, consequences of a lifetime spent living, and drinking, at full speed. He died at 47, liver shattered, a cautionary footnote to the era’s anthems of freedom.

Truman Capote: Martinis and Midnight Parties

Few writers rival Truman Capote’s mastery of cold observation and even colder drinks. The author of In Cold Blood and Breakfast at Tiffany’s confessed to a particular weakness for the Martini, the essence of sophistication in a single cocktail glass. Capote’s parties were legendary, his wit sharper than any lemon twist, but even he struggled to balance the glamour of public life with the shadows cast by addiction.

Capote’s decline was as dramatic as his novels. Plagued by professional disappointment and personal loss, he became more famous for his struggles than his stories in his later years, a narrative not lost on his admirers.

Hunter S. Thompson: Singapore Sling and Gonzo Nightmares

No inventory of hard-drinking writers is complete without Hunter S. Thompson, Gonzo journalism’s infamous wild child. While Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas reads like an extended hangover, its creation was powered by the Singapore Sling (with enthusiastic assists from mescal and beer chasers). Thompson drank not to mask or escape, but to intensify the chaos, riding the edge of the American Dream as it careened off the rails.

Inevitably, the relentless pace caught up with him. Thompson’s bravado masked deep disquiet; he died by suicide in 2005, a fittingly explosive conclusion to a life spent at full tilt.

Dylan Thomas: Whiskey Rage

Welsh poet Dylan Thomas made poetry sound like song and their recitation taste like whiskey. He adored the stuff, perhaps too much, rendering the line between inspiration and inebriation permanently blurred. His favorite drink, the pure Whiskey, was less a preference and more an occupational hazard.

Thomas’s passion became his poison. His spectacular drinking bouts in New York bars are the stuff of literary legend, but so too was his premature death, at 39, after one final, fatal binge. He became the archetype of self-destruction for an entire generation of poets.

Oscar Wilde: Absinthe and Aesthetic Afterglow

Oscar Wilde, wit, playwright, and style icon, found his match in Absinthe, the “green fairy” that beguiled and inspired Paris’s bohemian set. Wilde’s love for this potent, anise-flavored liquor was both fashionable and fateful. His sparkling, scandalous plays, including The Picture of Dorian Gray, often reflected the heady mix of liberation and danger found at the bottom of a glass of absinthe.

Wilde’s tragedies were manifold: public humiliation, imprisonment, exile, and lonely death. In many ways, absinthe was not just a drink but a metaphor for the excess that defined, and eventually destroyed, a dazzling career.

Dorothy Parker: Whiskey Sours and Acid Wit

Dorothy Parker, queen of the Algonquin Round Table and legendary wit, famously remarked, “I’d rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy.” Her favorite, the Whiskey Sour, was as sharp as her pen. Parker’s quips sliced through pretension and self-pity, yet beneath the banter was the unmistakable ache of disillusionment.

Parker’s alcoholism cost her dearly in terms of relationships and reputation. Nevertheless, her words, often composed and polished over a sour, remain as biting and relevant as ever.

Last Call

There was always more to these authors than their appetites, and it would be both trite and untrue to reduce their genius to the contents of their glasses. Yet, the drinks they favored shaped not just their evenings but, at times, their destinies and their prose. In the clink of ice and the blur of words, we catch glimpses of fragile humanity, perhaps the one thing these storied figures shared in equal measure with their readers.

So, next time you lift a glass, think of Hemingway in Havana, Fitzgerald on Long Island, or Wilde in Paris, and toast to the enduring power of literature, and the very mortal flaws of those who wrote it.