Long before cafés became trendy and gastropubs redefined dining, Europe’s taverns, inns, and osterias stood as the beating hearts of their communities. These weren’t just places to drink. They were courthouses and newsrooms, meeting halls and refuges, where kings rubbed shoulders with commoners and history unfolded over wooden tables worn smooth by centuries of elbows. Today, a remarkable handful of these establishments still serve patrons beneath the same timeworn beams and within the same ancient walls that welcomed travelers a millennium ago, offering modern visitors an intoxicating taste of living history.

The Dawn of Hospitality

In the emerald heart of Ireland, where the River Shannon cuts through the countryside, stands Sean’s Bar in Athlone, a pub with a foundation story that reaches back to the mists of the Dark Ages. Around 900 AD, a man named Luain Mac Luighdeach established an inn at what locals called Áth Mor, the Great Ford, a crucial crossing point for travelers navigating the Shannon’s rapid torrents. Luain served not merely as innkeeper but as guide, helping wayfarers traverse the treacherous waters safely. The settlement that grew around his hospitality came to bear his name, Áth Luain (the Ford of Luain), eventually evolving into modern Athlone.

What makes Sean’s Bar extraordinary beyond its ancient pedigree is the tangible proof hidden within its walls. During renovations in 1970, workers discovered that portions of the structure contained wattle and wicker construction dating to the ninth century, physical evidence of continuous occupation spanning more than eleven hundred years. Guinness World Records has recognized this weathered establishment as Ireland’s oldest pub, and quite possibly Europe’s most ancient drinking house still in operation. Today, visitors can still warm themselves by the fireplace where medieval chieftains once gathered, their feet scuffing the same sawdust-strewn floors that have absorbed centuries of stories, laughter, and song.

Across the Irish Sea, England harbors its own claimants to extreme antiquity. The Bingley Arms in Bardsey, near Leeds, traces its origins to between 905 and 953 AD, when it served as a priest’s house and hermitage for monks traveling to and from Bardsey Island. This humble beginning belies the establishment’s remarkable endurance through plague, reformation, and the countless upheavals that transformed medieval England into a modern nation. The building survived when the Black Death decimated English villages, and persisted when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries, adapting from religious waystation to public house while maintaining its essential character as a refuge for travelers.

Carved from Living Rock

Few establishments can match the dramatic setting of Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem in Nottingham, a pub literally carved into the sandstone caves beneath Nottingham Castle. While the existing structure dates from around 1650-1660, the caves themselves served as a brewhouse for the castle from at least the medieval period, possibly from 1067 when the Normans first erected the fortress. The pub’s evocative name and claimed 1189 founding date connect it to one of history’s most romantic episodes: the departure of King Richard the Lionheart and his crusader knights for the Third Crusade to the Holy Land.

Walking into this establishment means descending into a warren of rock-hewn chambers where the temperature remains perpetually cool and the atmosphere thick with centuries of accumulated legend. The higgledy-piggledy layout features cozy nooks carved directly from the cliff face, creating intimate spaces that have sheltered drinkers through nearly a millennium of English history. Among the pub’s curiosities hangs a dusty model galleon, reputedly 500 years old, which local superstition holds to be cursed. According to tradition, anyone who dares clean or touch the ship will die within three days, ensuring that the ancient vessel remains perpetually shrouded in cobwebs and grime, a peculiar monument to fear and folklore.

Continental Grandeur

The southern reaches of Europe boast their own temples to enduring conviviality. In the Renaissance jewel of Ferrara, Italy, Al Brindisi holds the distinction of being officially recognized by Guinness as Europe’s oldest osteria, with documented operation since 1435. Originally known as Hostaria del Chiuchiolino (derived from the local dialect word chiu, meaning drunk), this wood-paneled establishment attracted notable patrons from its earliest days. The great astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who studied in Ferrara, frequently enjoyed wine here, and according to local tradition, even lived in rooms above the osteria for a period. Walking through its doors today means stepping into an atmosphere little changed since the Renaissance, where dust-coated wine bottles line the walls alongside racks of whiskies and grappas, and plates of prosciutto are served with the same casual excellence that nourished scholars and merchants five centuries ago.

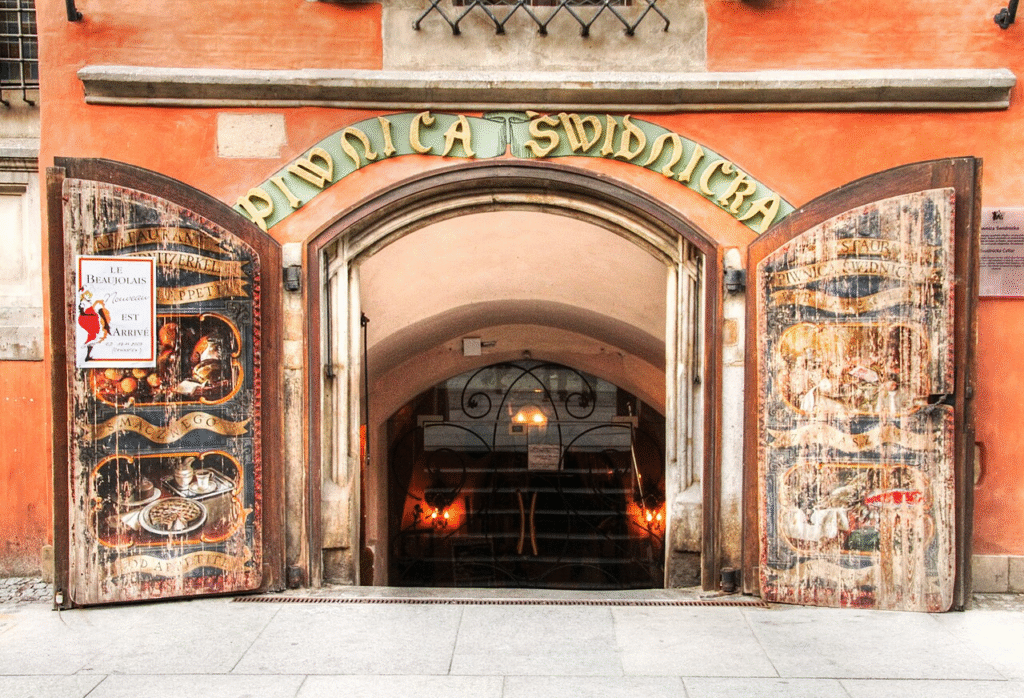

Even older is Poland’s Piwnica Świdnicka in Wrocław, established in 1273-1275 in the medieval cellars beneath the city’s Old Town Hall. This is not merely an ancient pub but Europe’s oldest continuously operating restaurant, a fact verified by solid documentary evidence including medieval invoices and receipts for beer deliveries. The establishment’s name derives from the nearby city of Świdnica, renowned in the Middle Ages as a brewing center whose dark, strong beer was delivered to prestigious “Świdnicka Cellars” in major cities throughout the region. Wrocław’s version alone survives today, its vaulted Gothic cellars having served countless generations through wars, occupations, regime changes, and the transformation of Central Europe. Though temporarily closed since 2017, with pandemic-related delays affecting reopening plans, the city-owned establishment awaits its return to active service, ready to add new chapters to seven and a half centuries of culinary history.

Royal Brews and Revolution

Munich’s Hofbräuhaus represents a different tradition entirely, one born not from humble travelers’ needs but from aristocratic decree. Duke Wilhelm V of Bavaria founded it in 1589 as the royal court brewery, producing beer exclusively for the ducal household and their guests. For nearly two and a half centuries, common citizens could only dream of tasting the legendary brews crafted behind the Hofbräuhaus doors. That changed in 1828 when King Ludwig I opened the establishment to the public, instantly transforming it into the center of Munich’s social and political life.

The Hofbräuhaus attracted a remarkable cross-section of European culture and politics. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart drank here, as did the future Empress Elisabeth of Austria, affectionately known as Sisi. Centuries later, Vladimir Lenin became a regular, with his wife praising the beer hall in her diary as the place “where the good beer wipes away all the differences between the social classes”. The establishment even became a revolutionary flashpoint when, on April 13, 1919, leaders of the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council proclaimed a new Communist Soviet Republic from its premises, triggering street battles that convulsed Munich for weeks. Today’s massive beer hall, with its communal tables and oompah bands, preserves the democratic spirit of those tumultuous decades while serving as the archetype of Bavarian beer culture recognized worldwide.

Literary Sanctuaries

Not all historic drinking establishments draw their fame from extreme age or royal patronage. Some earn their place in cultural memory through association with the creative minds who gathered within their walls. Oxford’s Eagle and Child, affectionately nicknamed “the Bird and Baby,” operated as an inn since the 1650s and became a pub in the 1680s, making it relatively young by the standards of this collection. Yet what transpired in its back room during the mid-20th century secured its immortality.

Beginning in the 1930s, a writing group called the Inklings began meeting regularly for Tuesday lunchtimes in a private lounge called the “Rabbit Room”. Here, in this modest space thick with pipe smoke and conversation, J.R.R. Tolkien would read drafts from The Lord of the Rings, while C.S. Lewis shared chapters of his Narnia chronicles. Fellow members including Charles Williams, Owen Barfield, and Hugo Dyson would critique, encourage, and debate, their discussions shaping some of the 20th century’s most beloved fantasy literature. The Inklings continued their Tuesday gatherings until 1962, when modernization destroyed the Rabbit Room’s privacy, forcing the group to relocate to the Lamb & Flag across St Giles’. The meetings ended entirely with Lewis’s death in 1963, but the Eagle and Child remains a pilgrimage site for readers worldwide who wish to stand where Middle-earth and Narnia first took shape.

The Enduring Appeal

What these establishments share transcends mere longevity. Each has survived because it fulfilled an essential human need for gathering spaces where social distinctions soften, where strangers become companions over shared drinks, and where the day’s burdens temporarily lift. Medieval travelers found shelter at Sean’s Bar and the Bingley Arms when the night was dark and roads were dangerous. Renaissance scholars like Copernicus found intellectual companionship at Al Brindisi. Revolutionary thinkers gathered at the Hofbräuhaus to debate the shape of society. Writers transformed the Eagle and Child into a creative laboratory that changed literature.

These historic bars and pubs persist because they remain fundamentally relevant. Sean’s Bar still welcomes Shannon River travelers, though they now arrive by car rather than on foot or horseback. Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem pours pints to tourists and locals alike in its sandstone caves. The Eagle and Child continues to serve Oxford’s students and scholars. They have adapted their offerings to modern tastes while preserving the essential character that made them community anchors centuries ago.

Drinking in the Weight of Years

Visiting these establishments offers more than excellent beer or atmospheric dining. Each represents a physical connection to the deep past, a tangible reminder that human nature remains remarkably consistent across the centuries. The conversations happening today over wooden tables at Sean’s Bar differ in specifics but not in essence from those conducted by medieval merchants and chieftains. The friendships forged at the Hofbräuhaus echo those formed when Mozart and his contemporaries gathered beneath its rafters. The creative energy that still fills the Eagle and Child connects directly to the Inklings’ Tuesday afternoon sessions.

Europe’s most ancient drinking establishments stand as monuments to continuity in an age obsessed with novelty. They remind us that some human institutions, the simple act of gathering to share drinks and conversation, prove so fundamentally valuable that they can endure plagues, wars, revolutions, and the endless churn of technological change. Their survival teaches a lesson worth savoring: the best ideas, like the best establishments, need not be new to remain vital. Sometimes the oldest solutions to human needs, refined across centuries of use, prove the most durable of all.

Header image: Sharon Flynn.

Feeling the buzz? Keep the good times flowing by tossing a tip in our virtual jar! Your support keeps the stories stirring, the jokes shaking, and the cocktails pouring. Click below to buy us a drink, and help fuel another round of Tipsy Times fun!