Oliver Reed’s life was a story written in bold, unruly script, one inked with performances of ferocious power, scars of hard living, and the legends that shadowed both his stardom and his downfall. In the pantheon of British actors notorious for their drinking, Reed belongs to a triumvirate alongside Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton, men as celebrated for their screen presence as for the chaos they sowed off it. Reed’s death, collapsed in a Maltese bar, halfway through shooting his final great film, Gladiator, was perhaps the only finale that could have suited a man who lived entirely without moderation.

Born to Perform, Destined to Rebel

Robert Oliver Reed was born in London on February 13, 1938, into a family already threaded through with stage and cinematic royalty. His uncle, Sir Carol Reed, was an acclaimed director, and his grandfather, Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, had been an influential actor and theater impresario. Such a pedigree provided Reed with a natural, if daunting, path to pursue in show business.

Reed’s upbringing, marked by his parents’ divorce and his mother’s revolving cast of lovers, introduced him to two lifelong companions: performance and alcohol. He later recalled playing barman at age four for his mother’s guests, an experience that blurred the lines between celebration and distress, and foreshadowed the turbulent decades to come.

Intensity, Scars, and Stardom

Reed’s acting roots ran deep; he began appearing as a film extra in his teens before landing his first significant break as Richard of Gloucester in The Golden Spur (1959). His career quickly gathered pace, with a standout lead in The Curse of the Werewolf (1961) and, soon after, critical praise for his menacing turn as Bill Sikes in the Oscar-winning Oliver! (1968), directed by his uncle.

Through the 1970s, Reed’s name became synonymous with roles demanding both gravitas and a certain animal charisma, such as Athos in The Three Musketeers (1973) and Porthos in The Man in the Iron Mask (1977). Both on and off screen, Reed’s presence was magnetic. His acting was marked by core intensity, physical strength, and an ability to embody danger or tenderness, sometimes in the same beat.

Yet Reed’s persona was defined as much by violence and excess as by artistic prowess. In 1963, he suffered a severe facial wound in a bar fight. Over 30 stitches left a scar that became part of his rugged, iconic visage. Far from derailing his ascent, this visual reminder of his off-screen exploits only sharpened his bad-boy mystique.

The Wild Man: Drinking, Scandals, and Infamy

Throughout his life and career, Reed’s drinking was not merely a hobby but a defining trait. His exploits became the stuff of folklore: rumors swirled of nights spent consuming legendary quantities: 60 gallons of beer, 32 bottles of scotch, 17 bottles of gin, and four crates of wine with friends (though Reed himself denied the numbers).

Alcohol fueled not just parties, but real mayhem. In 1964, Reed was viciously attacked at a nightclub, resulting in 63 facial stitches and a new, more hardened public image. In 1986, a drunken prank during a shoot in Seychelles led to his stand-in, Reg Prince, breaking his spine, bringing a lawsuit against Reed, who denied responsibility, but the tale cemented his notoriety.

Reed’s escapades extended to television as well. In 1975, during an appearance on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, he provoked actress Shelley Winters to pour whiskey over his head in response to inflammatory comments, and similar stunts became part of the public’s fascination with him.

Yet, for all his reputation as a “hellraiser,” those closest to Reed pointed out the complexity behind the image. His son, Mark, described him as “very mannered, intelligent, shy,” suggesting that Reed sometimes deliberately played up to his wild reputation, knowing it was what audiences and tabloids expected. Underneath the bravado, there was, it seems, a keen self-awareness and even vulnerability.

The Downward Spiral: Professional and Personal Consequences

As the years wore on, Reed’s drinking, combined with the habits formed by fame and expectation, began to undermine his career. He missed opportunities, most notoriously the chance to play James Bond, because his reputation rendered him too expensive or unpredictable to insure. As acting roles diminished, his drinking increased; as he landed parts, his drinking threatened their completion.

Things came to a head in 1995 while filming Cutthroat Island, when Reed was reportedly so drunk he exposed himself to co-star Geena Davis and was fired, replaced by another actor. Directors became wary of his volatility, and Reed found fewer chances in major films.

A Final Act

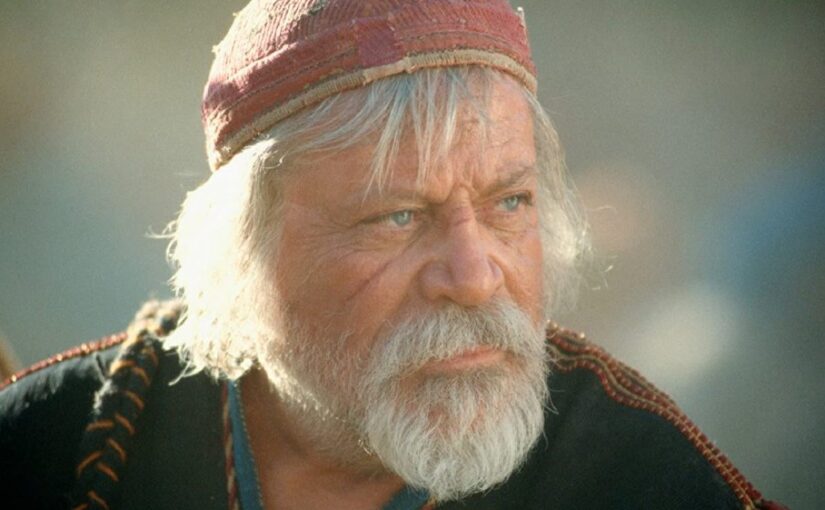

By 1999, Oliver Reed was 61 and, after years of hard living, physically diminished but still a formidable screen presence. Director Ridley Scott took a risk casting him as Proximo in Gladiator, the grizzled ex-gladiator who mentors Russell Crowe’s Maximus. Aware of Reed’s track record, Scott extracted a promise that Reed would abstain from drinking during filming.

The promise was short-lived. Reed reportedly stayed sober on set but couldn’t resist the lure of a local pub during shooting breaks. On May 2, 1999, amid a group of British Royal Navy sailors in Valletta, Malta, Reed engaged in a marathon drinking contest. He consumed three bottles of Jamaican rum, eight bottles of German beer, several double whiskies, and ran up a $435 tab before collapsing from a heart attack. He died en route to the hospital.

The Hole Left Behind

Reed’s death posed a challenge to the Gladiator team, as he hadn’t finished all his scenes. Rather than recast, Scott opted for an early use of CGI, mapping Reed’s face onto a double to complete his storyline, a testament both to his irreplaceability and to the industry’s respect for his contribution. The film, released in 2000, was a global success, and Reed’s portrayal of Proximo was posthumously celebrated, ensuring that his final role was one of his greatest.

Beyond the Legend

Oliver Reed’s life was a contradiction: a man drawn to chaos and misadventure, yet respected for his intelligence, sensitivity, and immense talent. He left behind stories as ferocious as his screen characters and performances as enduring as any in 20th-century British cinema. His legacy is not only that of the “last hellraiser” but also that of an actor who brought a dangerous edge to every role, and whose life, for better and worse, was truly lived at full tilt.

Drinking to the Grave

Reed once said, “I don’t have a drink problem. But if that was the case and doctors told me I had to stop I like to think I would be brave enough to drink myself into the grave.” In the end, bravado and reality met in tragic tandem. Yet for those who cherish the dangerous glamour of vintage British cinema, Oliver Reed’s flame, though short-lived, burns all the brighter for the wildness with which he fueled it.

Teaser image: Universal Studios